Website Technology

I wanted to write a few words about the technology used to create this website in case anybody stumbling across it might be curious. I feel this is also a good opportunity to give a little back to the community, since I leaned so heavily on community-sourced documentation and blog posts while creating this site.

Each of the software components used to create this website were chosen very carefully, and since I was going to be (lost) in the woods without a computer a majority of the time, I needed something very simple to maintain and very simple to update (from a cell phone). Also, since I’m not exactly building the world’s next great web app here, something simple would suffice. I considered Wordpress and similar options, but I wanted more control of the content and layout than Wordpress would allow, and ultimately, those solutions were overkill.

Jekyll

This website was developed using Jekyll, a static site generator. Static sites have no backend and no database, so this makes maintenance extremely simple. You write a few source files in one or more templating languages (Markdown, Textile, Liquid, or plain HTML), and the Jekyll engine (through a build process) constructs the website and outputs simple HTML, CSS, and JavaScript files. The output files can be hosted anywhere, and don’t need any backend to run.

There are other static site generators (and I tried several), but Jekyll is the most popular and most actively developed. The backend is written in Ruby, which I have no experience in, but luckily there is very little need to write any Ruby code (unless you need a custom plugin or something).

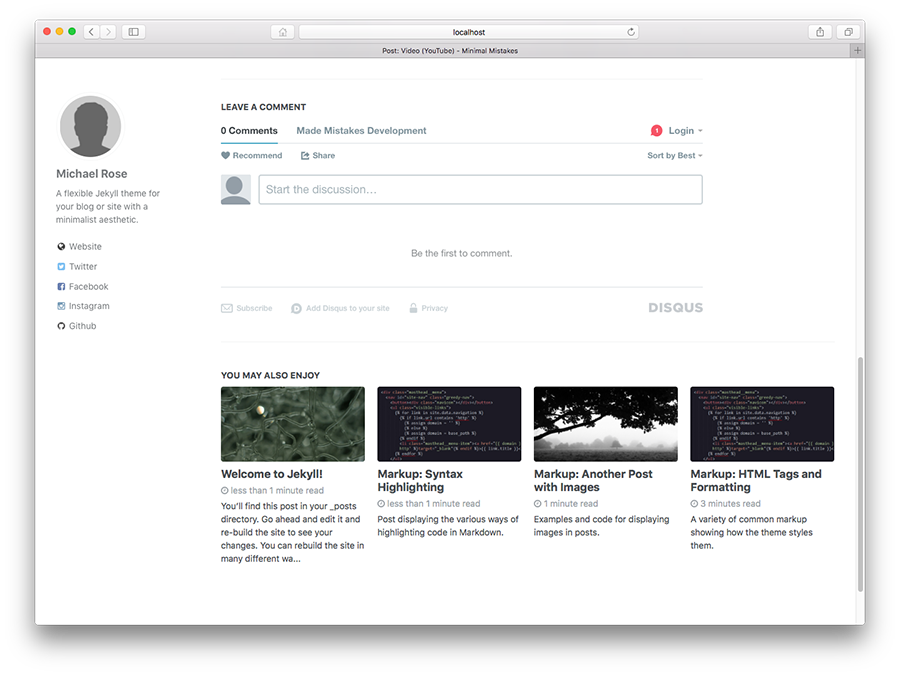

Most static websites can still take advantage of the many external web services out there (Google Maps, Simple Form, Disqus) for anything complicated. Finding good, free services is not always easy, but they do exist. Here is a good list.

GitLab Pages

The website is built and hosted on GitLab Pages. GitLab has a wonderful free CI build pipeline and hosting for small, static sites. The same is also available on GitHub, however GitHub does not allow any control over the build process and they only allow Jekyll to use a subset of whitelisted plugins. Since I wanted to write some build scripts in Python, GitHub wasn’t an option.

The GitLab build process is controlled by a .gitlab-ci.yml file placed in the root directory. Once checked into the GitLab repository, it initiates a build process on every commit following the instructions in the build file. Here is a sample GitLab build file similar to what I used:

prepare:

stage: build

image: python:3.6

script:

- commands to install Python dependencies and build data files used by the site

artifacts:

paths:

- _data/

pages:

stage: deploy

image: ruby:2.3

script:

- gem install bundler

- bundle install

- jekyll build -d public

artifacts:

paths:

- public

only:

- master

dependencies:

- prepare

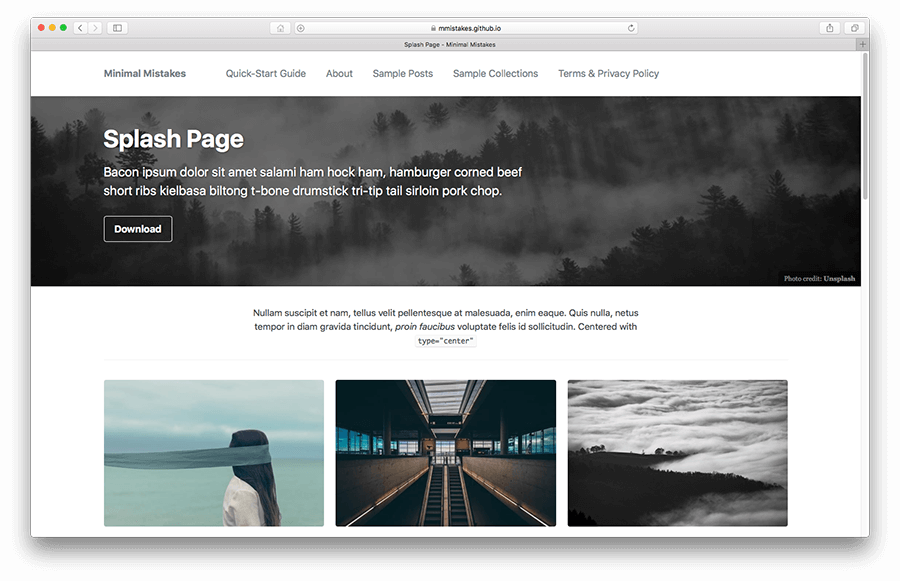

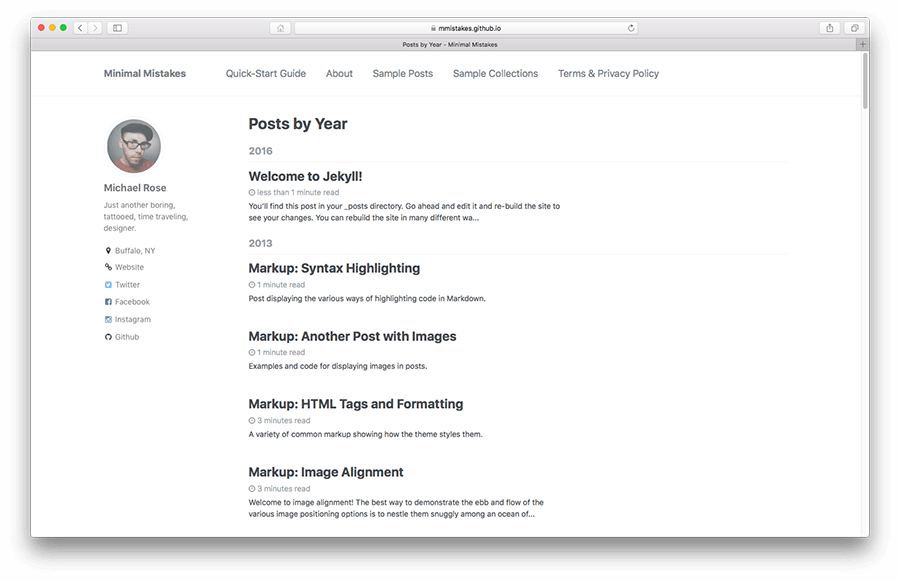

Minimal Mistakes

The next component (and probably the most important) is the fantastic Jekyll theme, Minimal Mistakes. I freely admit, I’m not very good with visual design, so having a theme that took care of 90% of the layout, colors, fonts, responsive scaling, etc was very important to me. Minimal Mistakes looks good, is responsive on small layouts (phones/mobile), and is under active development. It allows me to focus on the website content, and, for the most part, ignore any of the design headaches that you would find when rolling your own.

Machine Learning

From the very beginning, I wanted a feature on the site that could predict my progress as I hiked. While doing something simple (like calculating the pace and extrapolating) would be fine, I decided to use this as an exercise/excuse to practice several different ML techniques.

Python seemed like the natural choice, since Python has a robust set of ML libraries. Thanks to the decision to use GitLab, I was able to create my build pipelines in any language and format I wanted, so Python was available.

The only training data I really had was mileage and height difference between each checkpoint. If I record the date and time when each checkpoint is reached, then the time difference (in seconds) between each checkpoint can be used as the label for prediction. Then the unhiked segments could be predicted based on the elevation changes and mileage. Summing those up would result in a prediction, hopefully a good one. I also added a 10% buffer to the prediction to account for zero mileage days.

Since I did not have any real-world data (yet) to test my approach, I was worried it would not work very well once I started collecting real data. Optimizing a single model seemed dangerous, as it might work really well with fake data, but fail completely in the real world.

To somewhat mitigate this, the plan was to train several different regressors separately and combine the outputs in some way. I discovered a technique called stacking, which uses the output of each regressor as input (meta-features) to another simple regressor. The second level regressor is able to learn which first-level regressors are best at predicting different situations. This might be overkill for my use case, but it has the nice benefit of automatically minimizing contributions of any of the regressors that aren’t predicting well, which allows it to be very hands off and self-correcting as I get more training samples.

Here is a simplified version of the final code:

# Read in checkpoints CSV file into Pandas Dataframe

checkpoints = pd.read_csv(fileInPath, parse_dates=['dt_reached'], infer_datetime_format=True)

# Make a working copy of the data, and shift the rows so the diffs between rows can be computed

shifted = checkpoints.copy()

shifted['dt_reached_dt'] = shifted['dt_reached'].dt.date

shifted['to_spgr_shifted'] = shifted['to_spgr'].shift(1)

shifted['elev_shifted'] = shifted['elev'].shift(1)

shifted['dt_reached_shifted'] = shifted['dt_reached'].shift(1)

shifted['dt_reached_dt_shifted'] = shifted['dt_reached_dt'].shift(1)

# Compute the diffs

shifted['elev_diff'] = shifted['elev'] - shifted['elev_shifted']

shifted['mileage'] = shifted['to_spgr'] - shifted['to_spgr_shifted']

shifted['time_diff'] = shifted['dt_reached'] - shifted['dt_reached_shifted']

# Use rows that have completed dates to train the model, use the rest for prediction

# Notice we exclude calculating the overnight duration by filtering where out the dates are different

training = shifted[shifted['dt_reached_dt'] == shifted['dt_reached_dt_shifted']]

training = training[['elev_diff', 'mileage', 'time_diff']]

predict = shifted[pd.isnull(shifted['dt_reached'])][['elev_diff', 'mileage']]

# Extract features and labels

X_train = training.ix[:,0:2]

y_train = training.ix[:,2].map(lambda x: x.total_seconds())

X_predict = predict.ix[:, 0:2]

# Generate polynomial features (x1, x2, x1*x2, x1^2, x2^2)

poly = PolynomialFeatures(2)

X_train = poly.fit_transform(X_train)

X_predict = poly.fit_transform(X_predict)

# Create prediction objects. The number of folds for CV grows with the number of training rows to a max of 10

num_folds = min(round(len(X_train) / 10 + 1), 10)

regr = LinearRegression()

lasso = LassoCV(cv=num_folds, alphas=(1.0, 10.0, 20.0, 30.0, 40.0, 50.0), max_iter=10000)

ridge = RidgeCV(cv=num_folds, alphas=(1.0, 10.0, 20.0, 30.0, 40.0, 50.0))

elastic = ElasticNetCV(cv=num_folds, l1_ratio=[0.01, 0.05, .1, .3, .5, .7, .9, 1])

svr = SVR()

ada_dtr = AdaBoostRegressor(DecisionTreeRegressor(), n_estimators=500)

ada_knn = AdaBoostRegressor(KNeighborsRegressor(n_neighbors=round(len(training) / 5 + 1), weights='distance'), n_estimators=500)

estimators = [('regr', regr), ('lasso', lasso), ... ]

# Calculate error separately for all methods. The error is expressed in absolute mean hours.

errors = {}

for name, estimator in estimators:

estimator.fit(X_train, y_train)

predict[name] = estimator.predict(X_predict)

scores = cross_val_score(estimator, X_train, y_train, cv=num_folds, scoring='neg_mean_absolute_error')

errors[name+"_error"] = "{:.2f} (+/- {:.2f})".format(scores.mean() / 60 / 60, scores.std() / 60 / 60 * 2)

# Run a simple linear regression using all the 1st-level predictions as meta-features

stacker = LinearRegression()

prediction_cols = [e[0] for e in estimators]

stacker.fit(training[prediction_cols], y_train)

predictions = stacker.predict(predict[prediction_cols])

# Sum the predictions for all the remaining segments. Notice we add a 10% buffer to the estimate.

# This assumes 8 hours of hiking per day

predicted_time_to_finish_sec = predictions.sum()

predicted_time_to_finish_days = predicted_time_to_finish_sec * 1.1 / 60 / 60 / 8

# Average the predicted finish and estimated finish. This ensures the prediction doesn't get too crazy,

# especially in the first few weeks when there is little training data.

predicted_finish = checkpoints.ix[0, 'dt_reached'] + timedelta(days=predicted_time_to_finish_days)

estimated_finish = datetime.strptime('2017-09-01' , '%Y-%m-%d')

I hope you found this helpful! The whole website has been a blast to build and a good exercise for me. Thanks for making it this far!